Preface

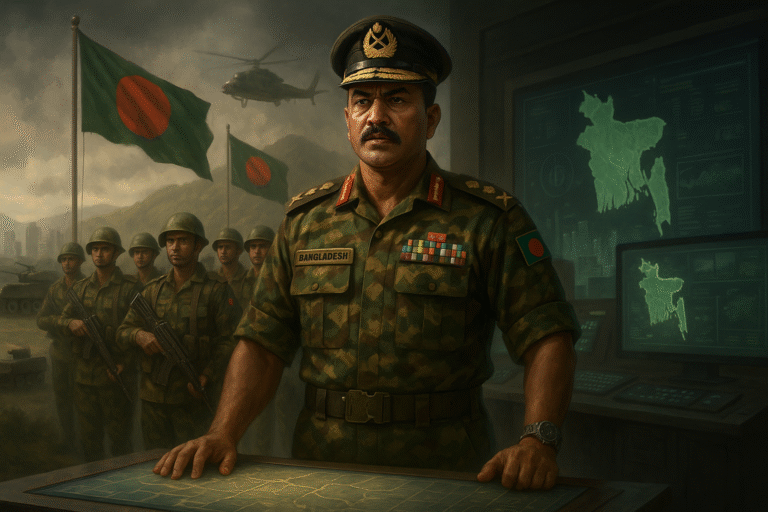

In the wake of the cataclysmic birth of Bangladesh in 1971—bathed in the blood of millions, punctuated by the cries of countless mothers and the defiance of an entire people—the formation of a national army was both a necessity and a paradox. The Bangladesh Army, born in a crucible of liberation, had to emerge swiftly from the embers of the Pakistan Army. But this birth was not immaculate. It carried within its DNA the very ethos, training, doctrine, and psychological imprints of the institution it had just violently separated from. The severed umbilical cord remained clumsily knotted—not cauterized—with time, politics, and history shaping what should have been a revolutionary people’s army into something quite different.

This book is about that paradox. It is about how a people’s war gave rise to a professional force, and how that force—despite the ideals of liberation—often acted in ways that undermined the spirit of the republic. It is about a nation’s civilian government repeatedly being manipulated, ill-advised, and overawed by its protectors. It is also about the taxpayers of this country—the farmers, workers, teachers, rickshaw pullers, and small business owners—who fund the military but are too often unaware of how it functions, whom it serves, and how deeply it continues to influence the nation’s course.

The Birth of the Bangladesh Army: A Struggle Within a Struggle

When Bangladesh emerged from the ashes of East Pakistan, it inherited very little in terms of military infrastructure. What it did possess, however, was the fierce dedication of a motley group of defected officers, paramilitary veterans from the East Pakistan Rifles (EPR), student volunteers, and members of the Mukti Bahini. They fought heroically during the nine months of the war, many trained in makeshift camps in India under the patronage of the Indian Army. The Mukti Bahini was not a conventional force—it was a guerrilla army, a resistance movement. Post-independence, the challenge was to forge a modern, structured, and professional military out of this diverse assemblage.

The Bangladesh Army’s foundation was laid with a deeply contradictory mandate. On one hand, it had to establish national defence, and on the other, it had to internalise values of democracy, constitutional obedience, and the supremacy of civilian authority. The irony, however, was that the architects of this new army were often the very officers trained and ideologically moulded by the Pakistan Army—a force with a notorious disdain for civilian supremacy.

The Umbilical Cord That Refused to Be Cut

The psyche of the Pakistan Army—rooted in a toxic mixture of colonial pride, anti-democratic tendencies, religious conservatism, and institutional arrogance—found its way into the bloodstream of the newly formed Bangladesh Army. Pakistani-trained officers, many of whom had served in East Pakistan or defected during the war, returned after independence with ambitions for prominence. Their professional training, laced with contempt for politicians and civilians, shaped the early culture of the Bangladesh Army.

This carried forward not only military tactics but also political attitudes. The seeds of militarism, planted deep in the ethos of the British-Indian colonial army and then transplanted into Pakistan’s structure, sprouted anew in Bangladesh. Although the uniforms had changed and the flag was now different, the command mentality, worldview, and ideological rigidity remained stubbornly familiar.

As a result, the relationship between the military and the civil administration in post-1971 Bangladesh was never one of harmonious coordination. It was one of suspicion, posturing, and hidden rivalries.

A Civil Administration Ill-Prepared and Ill-Advised

The civil government of independent Bangladesh—initially helmed by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and the Awami League—was overwhelmed by the monumental tasks of nation-building: rehabilitating millions of refugees, reconstructing war-ravaged infrastructure, and establishing constitutional institutions. In this fragile setting, civil governance suffered from inexperience, idealism without pragmatism, and a lack of technocratic capacity.

In this vacuum, the military quickly occupied a position of strategic and advisory dominance. Civilians, unsure how to handle matters of security, budget allocation for defence, or international military diplomacy, leaned heavily on generals, many of whom had little love for democracy. The military was not just an institution waiting for instruction. It was often the one issuing instructions, subtly shaping state policies and political alignments. In time, it learned to manipulate, manoeuvre, and override.

A series of ill-conceived recommendations—ranging from internal security arrangements to emergency governance—enabled the army to gradually entrench itself in the political and administrative machinery of the state.

Socio-Economic Fragility: The Weakest Link in National Security

A country’s defence structure should be reflective of its socio-economic realities. Bangladesh, in the early years, was a shattered economy. Millions were impoverished, food insecurity was rampant, healthcare systems were rudimentary, and literacy rates were abysmal. And yet, even in such dire straits, the military was prioritised with a disproportionate share of the national budget.

This was not just about national defence. It was about prestige, power, and the militarisation of national identity. The disconnect between the military’s growth and the country’s economic situation created a silent rift—a growing gap between those who bore arms and those who bore burdens.

This book argues that the military, in becoming an elite institution—highly subsidised, isolated in cantonments, and ideologically sequestered—has distanced itself from the very people it is supposed to serve. That distance has become a structural vulnerability in Bangladesh’s democracy.

The Pakistani-Trained Officer’s Lingering Shadow

This book pays special attention to the role of Pakistani-trained officers, not as individuals, but as the bearers of a particular institutional culture. These officers were often decorated, competent, and charismatic. But many of them also carried the baggage of authoritarianism, strategic paranoia, and Islamic militarism.

Their influence helped shape the doctrinal philosophy of the Bangladesh Army in its formative years. This influence affected everything—from civil-military relationships and command structures to political affiliations and intelligence practices. Even as new generations of officers entered the force, the inherited value system remained embedded through training manuals, officer colleges, and institutional narratives.

To date, echoes of this legacy remain. Whether in the form of coup rumours, excessive internal surveillance, or the army’s undeclared veto power over certain state decisions, the imprint of that early Pakistani model is hard to erase.

Why This Book Must Enter the Public Domain

Bangladesh is a democratic republic. However, democracy cannot be sustained solely by elections. It requires informed citizenry, transparent institutions, and the demystification of power structures. The Bangladesh Army has, for too long, operated beyond public scrutiny. It has enjoyed the reverence of heroism—some of it earned, much of it mythologised.

This book is not an attempt to vilify the army. Instead, it is a call to deconstruct, understand, and humanise it. It seeks to provoke debate—not division; to demand accountability—not anarchy. The people of Bangladesh have a right to know how one of the most powerful institutions in their country functions, who it serves, and how it has shaped the nation’s political trajectory.

The Era of Coups and Countercoups: Military Takeovers and Civil Collapse

Bangladesh has experienced repeated ruptures in its democratic journey. Between 1975 and 1990, the country was ruled, directly or indirectly, by military generals. The assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in August 1975 was not just a political tragedy; it was the opening act of an extended play in which the army became the kingmaker.

General Ziaur Rahman’s rise to power through military channels, his subsequent creation of a political party, and General Ershad’s autocratic rule for nearly a decade all indicate a recurring theme: that the military, once in power, rarely relinquishes it without a struggle.

This book scrutinizes how military takeovers were justified, how they were legitimized by fabricated ideologies, and how they permanently damaged the nation’s democratic fabric.

The Innocence of the Taxpayer and the Cost of Militarism

Every tank bought, every cantonment built, every overseas training program attended is paid for by ordinary citizens. But those same citizens are rarely consulted when the military decides to intervene in governance or manipulate internal politics. They are told to be proud, not curious. They are expected to pay but not to question.

This book asks: Where is the social contract? What happens when the protectors of the nation become arbiters of its destiny, without the consent of those who finance their existence?

The Bangladeshi taxpayer remains innocent, not just in action, but in awareness. This book aims to break that silence.

Why This Book—and Why Now

We are now more than half a century into Bangladesh’s life. The army is stronger than ever—its arsenal upgraded, its peacekeeping missions globally praised, its public image cautiously curated. Yet the issues of the past remain unresolved. The legacy of coups, the culture of secrecy, the disdain for civilian institutions, and the quiet consolidation of political power behind cantonment walls—all continue to haunt us.

This book is written not with the bitterness of an adversary but with the urgency of a patriot. It is written for students, academics, journalists, retired officers, political leaders, and—above all—the ordinary citizen.

It is a call to reflection. A call to reclaim the republic.

The narrative of this book does not seek to demonise. It seeks to dissect. It aims to inform, provoke, and perhaps, even heal. For a country to move forward, it must understand its past, not just the glorified parts, but also the uncomfortable truths.

Let this book be a beginning. Let it serve as an archive, an analysis, and an argument for reform. Let it remind us that the army must serve the people, not the other way around. And let it echo, through every page, the eternal truth that power without accountability is the enemy of freedom.

History of Military Coup d’État: From Ancient Regimes to 21st Century Power Grabs

Introduction

A coup d’état, commonly referred to as a coup, is the sudden and illegal seizure of a government, often executed by a small group of individuals, typically military or security elites. The term derives from French, meaning “stroke of state,” and throughout history, coups have been a recurrent method by which power changes hands, particularly in states with fragile institutions, discontented elites, or weakened civilian authority. Although often violent or coercive, coups can also occur without bloodshed and have sometimes been welcomed by segments of society as corrective or stabilising actions.

This article traces the historical lineage of military coups, beginning with antiquity through feudal monarchies, colonial empires, post-colonial state formation, Cold War clientelism, and culminating in the techno-authoritarianism of the 21st century.

I. Coups in the Ancient World

1. Assyria and Egypt

In the early civilisations of the Near East, political power was often contested through military force, albeit without modern concepts of the state. In Ancient Assyria, military leaders frequently vied for dominance, sometimes assassinating kings to assume the throne. Similarly, in Ancient Egypt, internal palace conspiracies often involved military officials or palace guards. The murder of Pharaoh Teti (6th Dynasty) is considered one of the earliest documented political overthrows, where his bodyguard may have killed a pharaoh.

2. The Roman Empire

Perhaps the most institutionalised model of military-driven power transitions occurred in Ancient Rome. Roman emperors often rose and fell by the will of the Praetorian Guard, an elite military unit tasked initially with protecting the emperor. Emperors like Caligula (AD 41), Pertinax (AD 193), and others were removed and replaced via palace coups.

The assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BC, although technically a senatorial conspiracy, was facilitated by discontent within Rome’s elite military and political class. As Tacitus later noted, “the army always made emperors”—a sentiment that echoed through imperial Rome’s turbulent centuries.

II. Feudal and Medieval Military Power Grabs

During the Middle Ages, political instability was marked more by feudal rebellions than formal coups, yet military usurpations were common.

1. Byzantium and the Palace Coups

The Byzantine Empire institutionalised palace coups as a form of succession. Between 395 and 1453 AD, nearly half of all Byzantine emperors were deposed through palace conspiracies, often involving generals and elite guards. Emperor Maurice was executed in 602 AD following a military revolt by Phocas, who seized the throne and began a new, albeit disastrous, reign.

2. Islamic Caliphates and the Mamluk Rule

In the Abbasid and later Ottoman periods, powerful military elites regularly toppled caliphs and sultans. The Mamluks—slave-soldiers of Turkic origin—eventually took control of Egypt in 1250, establishing their sultanate through an army coup against the Ayyubid dynasty.

III. Coups in the Age of Empire and Nation-States

1. Napoleon and the 18 Brumaire Coup

The modern term “coup d’état” gained prominence with Napoleon Bonaparte’s Coup of 18 Brumaire (November 1799), when he overthrew the Directory and established the Consulate, effectively ending the French Revolution and initiating military autocracy under republican guise. Napoleon’s rise demonstrated how military power could be cloaked in the rhetoric of national salvation.

2. Latin America and Caudillismo

In the 19th century, post-independence Latin American countries experienced a surge in military takeovers. Figures like Simón Bolívar and José de San Martín, while revered today, operated in a grey zone between military heroism and authoritarianism. Later caudillos such as Juan Manuel de Rosas (Argentina) and Antonio López de Santa Anna (Mexico) exemplified how militarism fused with populism and patronage to dominate political landscapes.

IV. The 20th Century: The Age of Ideological Coups

1. Post-World War Military Nationalism

After World War I, fragile new nation-states in Central and Eastern Europe witnessed military takeovers as nationalism surged. In Poland, Józef Piłsudski led the May Coup of 1926. Similarly, Mussolini’s March on Rome (1922), while not a classic coup, involved paramilitary intimidation backed by segments of the Italian army.

2. WWII and Military Regimes

In the prelude and aftermath of World War II, many coups were ideologically driven. In Japan, the attempted coup by the Imperial Way Faction in 1936 (February 26 Incident) reflects the militarist surge within fascist regimes.

After 1945, decolonisation and the Cold War created fertile ground for coups in Asia, Africa, and Latin America—regions where new nation-states emerged with weak civilian institutions and militaries that often saw themselves as guardians of national unity.

V. The Cold War and Military Coups as Proxy Tools

1. Africa

Africa’s post-colonial landscape was rocked by coups from the 1960s onward. In Nigeria alone, the military overthrew the government multiple times between 1966 and 1993. In Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah was toppled in 1966 while abroad, reflecting how fragile civil rule was amid economic decline and military resentment.

Colonial legacies left African armies as centralised institutions with logistical supremacy over fragmented civilian politics.

2. Latin America and CIA-Supported Coups

The United States and the Soviet Union both sponsored military takeovers to secure client regimes. In Chile, the most infamous case occurred in 1973 when General Augusto Pinochet, with CIA backing, overthrew elected socialist President Salvador Allende. Thousands were tortured and killed.

Argentina (1976), Brazil (1964), and Uruguay (1973) all fell under military juntas with tacit or open US support. The School of the Americas trained hundreds of Latin American officers in counterinsurgency and coup tactics.

3. Asia: South Korea, Indonesia, and Pakistan

South Korea experienced a coup in 1961 led by General Park Chung-hee, marking the beginning of decades of authoritarian rule that was often masked by economic development. In Indonesia, General Suharto seized power in 1965 following an alleged communist coup attempt, initiating one of the bloodiest anti-communist purges in history.

In Pakistan, General Ayub Khan’s 1958 coup marked the beginning of a long tradition of military dominance, later followed by Generals Zia-ul-Haq and Pervez Musharraf. Each justified their takeovers as stabilising acts, backed by either Islamic moralism or anti-corruption drives.

VI. The Late 20th to Early 21st Century: Coups Evolve

1. Soft Coups and Electoral Authoritarianism

Coups have evolved from overt tank-rolls to constitutional coups, where military-aligned judges, intelligence services, or manipulated parliaments engineer the removal of civilian leaders.

In Thailand, the military has staged at least 13 coups since 1932, including in 2006 and 2014. In Turkey, coups occurred in 1960, 1971, 1980, and 1997—the last one labelled a “post-modern coup” due to its non-violent, media-driven nature.

2. Failed Coups and Civil Resistance

The failed 2016 coup attempt in Turkey is emblematic of how coups now face resistance from civilian mobilisation and mass media. President Erdoğan, alerted via FaceTime, called on supporters to rally, turning the tide against the putschists. The event showed how digital communication can both hinder and help coup attempts.

In Venezuela (2002), Hugo Chávez survived a coup attempt thanks to loyalist military elements and popular mobilisation, reflecting the increasingly polarised nature of modern coups.

VII. The 2020s: Coups Resurging in Fragile States

1. Africa’s Coup Belt

Between 2020 and 2024, West Africa experienced a surge in military takeovers, with Mali (2020 and 2021), Guinea (2021), Burkina Faso (2022), Niger (2023), and Gabon (2023) being the notable instances. These coups reflect a backlash against corrupt or ineffective governance, jihadist insurgencies, and disillusionment with democracy.

These coups—often bloodless and celebrated by some sectors—also reflect the enduring allure of military “order” over messy democratic politics.

2. Myanmar 2021: Return of the Junta

In February 2021, Myanmar’s military once again seized power, detaining civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi and igniting widespread protests. The military’s justification? Alleged electoral fraud. Its result? Civil war, international condemnation, and economic collapse.

3. Russia’s Wagner Revolt (2023)

While not a formal coup, Yevgeny Prigozhin’s short-lived mutiny against Vladimir Putin in June 2023 illustrates how paramilitary power and elite rivalries can threaten established regimes, even in strong states. The quashing of the revolt reaffirmed Putin’s grip, but exposed vulnerabilities in military cohesion.

Conclusion: Anatomy and Future of Coups

From Pharaoh’s court to cyberspace, the coup d’état remains a potent tool for seizing elite power. While the methods have changed—from palace intrigues and barracks mutinies to constitutional manipulation and information warfare—the underlying drivers persist: institutional weakness, elite factionalism, economic failure, and foreign meddling.

Today, as global democracy retreats and authoritarian populism rises, the risk of coups remains high in states where the military is politicised, civilians are fragmented, and justice systems are co-opted.

Understanding coups is essential not only for historians and political scientists but for citizens committed to safeguarding democracy.

Selected References

Primary Sources:

-

Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Civili, 49–48 BC.

-

Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, ca. 121 AD.

-

Tacitus, Annals, ca. 116 AD.

-

Constitution of the Roman Republic (Historical fragments).

Secondary Sources:

-

Huntington, Samuel P. The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil–Military Relations. Harvard University Press, 1957.

-

Finer, S. E. The Man on Horseback: The Role of the Military in Politics. Routledge, 1962.

-

CoupCast Database, University of Central Florida (https://coupcast.com)

-

Alagappa, Muthiah. Coercion and Governance: The Declining Political Role of the Military in Asia. Stanford University Press, 2001.

-

Perlmutter, Amos. The Military and Politics in Modern Times. Yale University Press, 1977.

-

Levitsky, Steven & Ziblatt, Daniel. How Democracies Die. Crown Publishing, 2018.

-

The Global State of Democracy Report, International IDEA (2022)

-

Gowan, Richard. “UN Peacekeeping and Military Coups.” Foreign Affairs, 2023.

-

The Wilson Centre: “Latin America’s Lost Decades and Coup Patterns” (2021)

-

Reuters Special Report: “From Mali to Gabon: Africa’s Coup Trend Returns” (2023)

The Necessity of Writing History: Towards a Candid Historiography of the Bangladeshi Military

Introduction

History is not merely the accumulation of dates, events, and personalities—it is the soul of a nation rendered in words, memory, and legacy. In every civilisation that has endured, history has served not only as a mirror to the past but as a compass for the future. When written earnestly and interpreted critically, it enables societies to understand themselves, confront their errors, and recalibrate their course.

In this context, the urgent need to write the history of the Bangladeshi military—with objectivity, impartiality, and candour—becomes a national imperative. Bangladesh’s military has been central to the nation’s formation, consolidation, crises, and identity politics. And yet, its historical narrative remains fragmented, often cloaked in myth, ideology, or institutional reticence.

This essay examines why the act of writing history—and, more precisely, the creation of a responsible historiography of the Bangladeshi military—is crucial for future generations and the global understanding of Bangladesh as a modern state. It lays out the philosophical, civic, scholarly, and ethical arguments for such an endeavour.

The Meaning of History and Historiography

Before turning to Bangladesh, it is necessary to distinguish history from historiography.

-

History is the study of past events.

-

Historiography is the writing of history: the choices made by the historian, the methods used, and the lens through which facts are interpreted.

History is what happened. Historiography is the process by which we understand and frame what happened. And therein lies the power—and responsibility—of the historian. Through selective emphasis or omission, interpretation or judgment, history can be manipulated to inspire, justify, divide, or deceive.

In Bangladesh, where political polarisation infects almost all domains of public life, historiography is more than academic—it is ideological. Hence, the need for a non-committal, impartial, and candid account of the military becomes all the more vital.

Why History Must Be Written

1. Preserving Collective Memory

Nations that forget their past are condemned to repeat their errors. The act of writing history preserves collective memory—not just of victories and glory, but also of failures, betrayals, and silences. In Bangladesh, where oral culture often supersedes documented history, memories of pivotal moments such as the 1971 Liberation War, the 1975 military coup, or the 2009 BDR mutiny are passed down with emotion but not always with accuracy.

Without documentation, myths replace facts. A proper military historiography can prevent the distortion of national memory and help future generations distinguish between legend and lived experience.

2. Holding Power Accountable

One of the most significant values of history is that it can act as a check on power. When institutions know their actions will be recorded, scrutinised, and remembered, they behave differently. A military that operates in the shadows—out of civilian oversight or public scrutiny—can develop cultures of impunity.

A documented, impartial history of the Bangladeshi military can serve as a form of civic accountability. It can force reflection on past actions, strategic errors, political interventions, and institutional biases. It can ask hard questions that even commissions and inquiries hesitate to raise.

3. Enabling Public Discourse

Military matters in Bangladesh are often viewed as off-limits for public discourse. Whether out of fear, reverence, or ignorance, the public generally lacks the tools or confidence to question or critique military policy, budgets, or interventions.

An open, candid historical record can demystify the military’s role. It can educate citizens, not to undermine their armed forces, but to understand them. It can cultivate an informed discourse on civil-military relations, national security, and the values that underpin a people’s army in a democratic republic.

Why the Military History of Bangladesh Must Be Written

1. The Military as a Political Actor

Since 1971, the Bangladeshi military has not merely served as a defence force—it has been a political actor. The tragic assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1975, followed by a string of military regimes under Ziaur Rahman and later H. M. Ershad, shaped the trajectory of the nation.

Yet much of this history is either sanitised or selectively glorified. Ziaur Rahman’s rise, for example, is still narrated through partisan prisms—either as a heroic nationalist or as a power-grabber complicit in political purges. Only impartial historiography can offer balance and nuance.

Furthermore, the military’s role in subsequent events, such as the 2007–08 caretaker government crisis or its strategic influence under successive regimes, remains under-examined. Writing history would enable scholars and citizens alike to understand how and why the military became involved in politics, and what the long-term consequences were.

2. Understanding Civil-Military Relations

Bangladesh’s civil-military relations have always been precarious. While democratic institutions have nominally functioned, the military has often been the shadow force behind major policy decisions. The fear of another coup or military “intervention” has loomed over nearly every civilian administration.

A historical record of these dynamics can shed light on the tensions, miscommunications, and power struggles that have plagued the relationship between elected leaders and uniformed generals. It can help prevent future misunderstandings by learning from the past.

3. Regional and Global Relevance

In a region where militaries often dictate terms—Pakistan, Myanmar, Thailand, Bangladesh’s military history is of interest not just domestically but globally. How did a new army born out of a guerrilla struggle evolve into a professional force? How did its Pakistani colonial roots affect its doctrines? Why did it abandon coups after 1990, unlike its neighbours?

Answering these questions through rigorous documentation enriches global comparative studies in political science, security studies, and postcolonial statecraft. Bangladesh’s story becomes part of the broader tapestry of nations negotiating the military’s place in democratic life.

How History Should Be Written: The Ethos of Non-Commitment and Candour

Writing history is not just about what is written, but also how.

1. Non-Committal Does Not Mean Neutrality to Injustice

Non-committal historiography means refusing to write from a partisan perspective. It does not mean moral blindness. When the army commits wrong—be it suppressing uprisings, committing rights abuses, or overthrowing democracy—it must be recorded. When it acts heroically—defending the nation, saving lives, upholding law and order—that too must be recognised.

Truth, not loyalty, must be the compass of the historian.

2. Impartiality Through Multivocality

An impartial history includes multiple voices—not just generals and politicians, but sepoys, victims of military excesses, family members of slain officers, journalists, and bureaucrats. It is only through such mosaic storytelling that balance can be achieved.

Too often, military history is told from a top-down perspective. The aim must be to democratise historical writing—to open the space for narratives from below.

3. Candour as Intellectual Honesty

There must be honesty about uncomfortable truths: how caste and class affect recruitment and promotions, how Islamist or nationalist ideologies pervade the ranks, how defence budgets are inflated without transparency, how ex-officers influence civil policy and business, and how, even in peacekeeping missions, misconduct can occur.

Candour is not disloyalty. It is the highest form of patriotism—truth in the service of national maturity.

The Cost of Silence

In Bangladesh, silence is often considered safer than speech, especially when it concerns powerful institutions. But silence has a cost.

-

Generations grow up uninformed, susceptible to propaganda.

-

Errors are repeated because the lessons of history are not studied.

-

Justice is denied because abuses are forgotten or covered up.

-

Citizens disengage, believing the military to be beyond their reach or understanding.

In the long run, this fosters a culture of fear, apathy, and disconnection. Democracy cannot flourish in such soil.

History for Future Generations

Future generations of Bangladeshis—be they scholars, soldiers, or statesmen—deserve access to their history. They deserve to know not just what happened, but why and how it happened. They deserve a record untainted by party loyalties or institutional gatekeeping.

Writing military history now—with the benefit of 50 years of hindsight—is both a duty and an opportunity. It is a chance to pass down a record not just of battles and uniforms, but of decisions, dilemmas, betrayals, and sacrifices.

It is an opportunity to instil resilience, responsibility, and reflection into the DNA of the republic.

Conclusion

History, at its best, is the conscience of a nation. In documenting the history of the Bangladeshi military in a non-committal, impartial, and candid way, we are not waging war against any institution—we are waging peace with truth. We are ensuring that power, when wielded, is accountable. That legacy, when claimed, is earned. That patriotism, when invoked, is not blind.

To write this history is to reclaim the right to understand ourselves. And in that understanding lies the possibility of becoming something better.

Let the pen not fear the uniform. Let history be written.

Why the Bangladesh Army Repeatedly Sought Power: A Critical Analysis of Militarism, Ideological Inheritance, and the Betrayal of Democratic Aspirations

Introduction

The formation of the Bangladesh Army in 1971 marked the emergence of a military force born not from colonial strategy but from a people’s liberation struggle. One might have expected this army, emerging from the trenches of freedom, to champion democracy, transparency, and civilian supremacy. Yet, in the subsequent decades, the Bangladesh Army demonstrated an undeniable tendency to seize power, manipulate political transitions, and marginalise elected civilian authority.

This essay explores the reasons behind this paradox: why did the Bangladesh Army, forged in the fires of a democratic uprising, consistently betray the national aspiration of democracy? Was it institutional culture, ideological inheritance from Pakistan, or the result of coercion and manipulation by external and internal elites? Or was it a deeper, insatiable thirst for power embedded in its officer corps and strategic doctrine?

To answer this, the essay analyses the structural, psychological, and geopolitical factors influencing the army’s interventions and its failure to support, let alone strengthen, democratic consolidation in Bangladesh.

1. Birth of the Bangladesh Army: A Contradictory Genesis

The Bangladesh Army was established during the 1971 Liberation War. Initially comprising defected officers from the Pakistan Army, East Pakistan Rifles (EPR), and members of the Mukti Bahini, the army emerged as a patriotic force fighting for sovereignty and democratic liberation.

However, many of its founding officers were initially trained in the Pakistan Military Academy (PMA) and steeped in its colonial, anti-democratic, and hierarchical values. This Pakistani military tradition viewed civilian politicians with contempt, perceived democracy as chaotic, and considered military governance a guarantor of “order.” These values would later infiltrate the newly formed Bangladesh Army.

Despite the people’s cry for “সংবিধান, গণতন্ত্র, ও নাগরিক অধিকার” (Constitution, Democracy, and Civil Rights), the army harboured within itself an elite that saw governance as their natural entitlement, especially as the civilian government of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman struggled to manage the post-war state.

2. Ideological Inheritance from the Pakistan Army

The Pakistani military ethos was deeply influenced by:

-

British colonial martial traditions.

-

Anti-politician sentiments.

-

Strategic paranoia about India.

-

The notion of the military as a guardian of national ideology.

Most of the officers who defected to form the Bangladesh Army—such as Ziaur Rahman and Khaled Musharraf—were commissioned by Pakistan and brought with them an ingrained belief in the military’s superiority over civilian institutions.

Moreover, the Pakistani Army’s practice of shaping the nation through direct rule (Ayub Khan, Yahya Khan) left a lasting blueprint. Bangladesh’s early army officers had seen how military rulers in Pakistan had commanded international respect, economic discipline, and bureaucratic efficiency—however misleading that image may have been.

This institutional memory became a template for action. The army did not just inherit infrastructure from Pakistan—it inherited ideological DNA.

3. Structural Weaknesses of the Civil Government

From 1972 to 1975, Sheikh Mujib’s government faced overwhelming challenges: famine, economic collapse, internal dissent, and external interference. The Awami League’s political machinery, hastily adapted from its movement days, was not prepared for statecraft.

The army, meanwhile, had structure, discipline, and organisation. In the face of bureaucratic chaos and political infighting, many in the military saw themselves as the only institution capable of competence within the state.

Rather than assisting in democratic institution-building, the military positioned itself as a parallel state. It became common in cantonments to hear mutterings like “rajniti baaje” (politics is bad), or “shashon e amader dorkar ache” (we are needed to govern).

The failed implementation of BAKSAL (one-party rule) and the creation of paramilitary forces, such as the Rakkhi Bahini, further alienated the army. Many officers viewed the political leadership as self-serving, paranoid, and authoritarian—ironically, sentiments they would later come to embody themselves.

4. The 1975 Assassination and the Military Takeover

On August 15, 1975, a faction of mid-level army officers orchestrated a brutal coup, assassinating Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and most of his family. This marked the army’s first direct seizure of political power.

While General Ziaur Rahman did not plan the initial coup, he quickly capitalised on the political vacuum, emerging as the de facto leader by late 1975. Under Zia, the army began its formal entry into politics, with the creation of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) in 1978. Zia’s dual role as a military leader and political architect established a precedent of military populism—a dangerous hybrid in which the gun and ballot were wielded by the same hand.

This was not a response to a national crisis—it was an opportunistic appropriation of the democratic space. Zia utilised nationalist slogans, anti-India sentiment, and military networks to consolidate power. His rule was followed by that of General Ershad, who seized power in 1982 and remained in power until 1990. Together, Zia and Ershad ruled for 15 of Bangladesh’s first 20 years through military coups, martial law proclamations, and manipulated elections.

5. The Military’s Strategic Interests in Governance

Why did the army feel it had to govern? Several factors explain the army’s consistent push for political power:

a. Institutional Self-Preservation

Governance gave the army control over defence budgets, appointments, international military cooperation, and internal promotions. It allowed the senior brass to entrench themselves economically through the establishment of trusts, real estate projects, banks, and corporations like Sena Kalyan Sangstha, Trust Bank, and the Army Welfare Trust.

b. Geopolitical Leverage

Both India and the United States, for different reasons, were often willing to accommodate military regimes if they ensured regional stability. During the Cold War, military rulers were frequently courted by both capitalist and socialist blocs. Zia and Ershad leveraged this to gain foreign legitimacy despite domestic repression.

c. Civilian Disunity

Successive civilian politicians failed to present a united front. Infighting between the Awami League and the BNP, along with weak democratic institutions, meant that even during periods of civilian rule, the military retained de facto control over strategic matters.

6. The Failure to Support Democratic Consolidation

Even when the army was not in direct power, it often acted as a political kingmaker. The 2007–08 military-backed caretaker government suspended democratic processes under the guise of “corrective governance.” While elections were eventually held, the interim regime facilitated a structural shift in power, laying the groundwork for future political manipulation.

Why did the military not support the growth of democratic checks and balances?

-

Suspicion of Politicians: The belief that politicians are corrupt, divisive, and ineffective remains deeply ingrained in military thinking.

-

Lack of Civilian-Military Dialogue: Civilian leaders rarely engage in policy dialogue with military institutions, which fuels alienation.

-

Education and Socialisation: Military training in Bangladesh—especially at the academy and staff college levels—does not prioritise constitutional literacy, human rights education, or the principles of democratic governance.

7. Was the Army Coerced or Influenced?

The question arises: Did the military intervene because it was coerced or manipulated by others?

a. Foreign Influence

There is credible evidence that external actors—especially during the Cold War—encouraged military takeovers. Zia’s rise was quietly backed by Western powers interested in a non-socialist Bangladesh. Later, international development agencies often preferred dealing with military regimes due to their efficiency and centralisation.

b. Domestic Elites

Civil bureaucracy, corporate lobbies, and sections of the judiciary often welcomed military rule for stability and predictability. These elites did not coerce the army, but they certainly emboldened it.

c. Internal Ideological Motivation

Ultimately, however, the military’s thirst for power appears to be more self-driven than externally coerced. The institutional culture of superiority, the disdain for democratic pluralism, and the lure of unchecked power were primary motivators.

8. Post-1990 Transition and Lingering Shadows

Following the ousting of Ershad in 1990, Bangladesh returned to civilian rule. But the army did not retreat entirely. It maintained influence through intelligence networks (DGFI), peacekeeping deployments (used as carrots for loyalty), and informal influence over national security and political transitions.

Even today, the army plays a crucial role behind the scenes. While coups have become less likely, political engineering, surveillance, and subtle intimidation remain part of the army’s unofficial arsenal.

Conclusion

The Bangladesh Army’s repeated interventions in politics and its failure to support democratic institution-building are the products of multiple intersecting forces: colonial legacies, ideological inheritance from Pakistan, structural advantages over civilians, and an unquenchable thirst for control.

This is not to deny the army’s legitimate role in defending the nation or its sacrifices in war and disaster response. But these contributions do not entitle it to govern.

For Bangladesh to realise its foundational dream—a secular, democratic, just republic—the military must undergo profound introspection. Its history must be written, its past questioned, and its future redefined in service to the constitution, not the cantonment.

Bibliography

Books and Academic Sources

-

Huntington, Samuel P. The Soldier and the State. Harvard University Press, 1957.

-

Finer, S. E. The Man on Horseback: The Role of the Military in Politics. Routledge, 1962.

-

Mascarenhas, Anthony. Bangladesh: A Legacy of Blood. Hodder & Stoughton, 1986.

-

Riaz, Ali. Inconvenient Truths about Bangladeshi Politics. Routledge, 2022.

-

Ahmed, Nizam. Civil-Military Relations in Bangladesh: Military Rule and the Quest for Democracy. University Press Limited, 2001.

Journals and Articles

-

Jalal, Ayesha. “The State and Military in Pakistan.” Asian Survey, Vol. 24, No. 5, 1984.

-

Riaz, Ali. “Bangladesh’s Democratic Backsliding and the Role of the Military.” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 30, No. 4, 2019.

-

Siddiqa, Ayesha. “Military Inc.: Inside Pakistan’s Military Economy.” Oxford University Press, 2007 (referenced comparatively).

News and Reports

-

The Daily Star Archive (1975–2024)

-

Human Rights Watch Reports on Bangladesh Military Interventions

-

Al Jazeera and BBC South Asia Files on Caretaker Government (2007–08)