The year 1971 is etched in the collective memory of millions of Bengalis as a year of unbearable loss, unspeakable suffering, and at the same time, the beginning of a dream—a free Bangladesh. As the Pakistan Army unleashed one of the most brutal genocides of the 20th century, more than ten million men, women, and children fled for their lives, crossing the border into India. What awaited them was not comfort or certainty, but a painful, humiliating existence in refugee camps set up across the border. Yet, in these camps, life persisted—through hunger, fear, disease, and despair, the human spirit found ways to hold on.

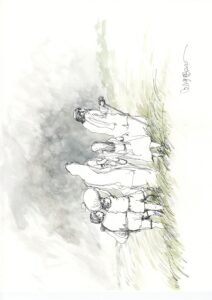

The Long March to the Unknown

Leaving everything behind—homes, land, possessions, and memories—families began their desperate journey. Men, women, and children carried what little they could on their heads and shoulders. The journey was harsh, the paths unknown, and death followed them closely. Many perished on the way, and those who survived reached the border hoping for safety, but not knowing what lay ahead.

The first painting depicts this very march. Men with walking sticks, women with children on their hips, and tired, barefoot children walking through dusty trails. Their faces are empty, their future uncertain, but they continue moving forward.

Survival in Makeshift Camps

Upon arrival, families were huddled into tiny bamboo or tarpaulin tents, often 10×10 feet spaces meant for five or more people. The air inside was suffocating, the heat unbearable. Mosquitoes, flies, and disease were constant companions. Food was scarce, water scarcer. Relief supplies from the Indian government, humanitarian agencies, and local Indian villagers trickled in, but never enough to meet the demand.

One of the uploaded images titled “ক্যাম্পে আমাদের পাঁচ জনের জন্য ব্রাদ্দকৃত ঘর ১০ বাই ১০ ফুট” (Our 10×10 Room in the Camp) shows the cramped conditions where a family of five lived—a cruel mockery of privacy, hygiene, or dignity.

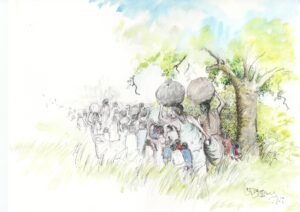

Fetching Firewood for Survival

Food was rationed, but cooking fuel was the next big challenge. Women and children ventured deep into the jungles to cut firewood, often risking snake bites or injuries. The image titled “জঙ্গল থেকে লাকড়ি কেটে আনছি রান্না করার জন্য” (Fetching Firewood from the Jungle) captures a woman gathering dry twigs and wood—her back bent, body fatigued, yet determined to feed her family.

Nursing Freedom Fighters in Refugee Hospitals

Many refugee camps had makeshift hospitals or wards for injured Mukti Bahini fighters. Local volunteers, men and women alike, worked tirelessly to provide care. One of the paintings, “জয় বাংলা ওয়ার্ড এ মুক্তি জোদ্ধাদের সুশ্রসা করছি” (Tending Freedom Fighters in the Joy Bangla Ward), shows young volunteers providing comfort and food to the wounded. In these moments of service, many refugees found purpose beyond their misery.

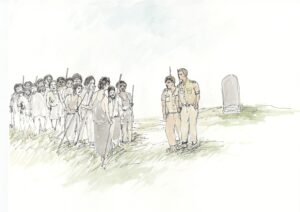

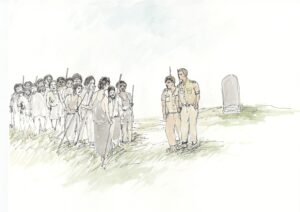

The Birth of the People’s Army

In these camps, young men and women lined up for military training to join the Mukti Bahini. The painting titled “ফোর ইস্ট বেঙ্গল মুক্তি ফৌজ প্রশিক্ষন দিচ্ছে ২৫সে মার্চের পর” (4 East Bengal Regiment Training Freedom Fighters After March 25) depicts hundreds taking up bamboo sticks as part of their first lessons in defence, preparing for guerrilla warfare. It was not just survival anymore; it was about fighting back.

Running from Aerial Bombardments

The Pakistani Air Force targeted border villages and refugee settlements in air raids. Families ran into muddy swamps, hiding under filthy water to save their lives. The painting “বিমান হামলা থেকে জীবন বাঁচানোর জন্য পচা ডোবায় আশ্রয় গ্রহন” (Taking Shelter in a Stinking Swamp During Air Raids) is a chilling portrayal of human survival instinct. Children, women, and elders huddled together, half-submerged in mud and water, clinging to life.

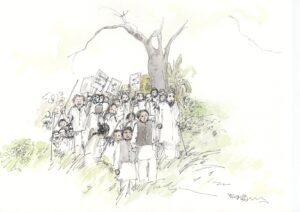

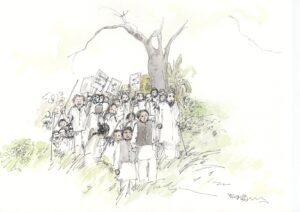

Cultural Resistance and Spirit

Even in the darkest hours, cultural life refused to die. In refugee camps, people organized drama performances, music nights, and recitations to uplift the spirit of the community. “র্যিফুজি ক্যাম্পে আমাদের সাংস্কৃতিক দল অনুশীলন নিচ্ছে” (Our Cultural Team Rehearsing in the Refugee Camp) and “মেলাঘর মুক্তি বাহিনী ক্যাম্পে সাংস্কৃতিক অনুষ্ঠান করে বিনোদন দিচ্ছি” (Cultural Program for Entertainment at Melaghar Mukti Bahini Camp) illustrate the resilience of refugees who found joy in art and music despite their shattered lives.

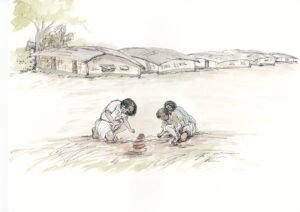

Daily Struggles of Camp Life

Simple acts like fetching water or preparing food became monumental tasks. One of the sketches “র্যিফুজি ক্যাম্পে আমাদের থাকার রুম” (Our Room in the Refugee Camp),shows a woman, bucket in hand, stepping out to fetch water. Behind her, the bare bones of camp life—a bed, hanging clothes, and an open door revealing the vast emptiness outside.

Entertainment as Escape

Makeshift open-air theaters became community centres of hope, where refugees gathered to watch performances. “মেলাঘর মুক্তি বাহিনী ক্যাম্পে সাংস্কৃতিক অনুষ্ঠান করে বিনোদন দিচ্ছি” (Open Air Cultural Event at the Melaghar Camp) shows hundreds sitting under trees, watching a stage play titled “জেলা গ্রাম” (District Village)—a brief escape from their painful reality.

The Last Mile—Returning to the Homeland

The final painting, “বিমান হামলার পর ঘর ছেড়ে পলায়ন করছি” (Fleeing After an Air Raid), captures the moment when families, sensing the end of war approaching, prepare to return to their devastated villages. Fear still lingers, but there is a flicker of hope in their eyes—a hope to rebuild, to reclaim dignity, and to begin anew.

Closing Reflections

The refugee experience of 1971 was not just about displacement—it was about transforming despair into resistance, suffering into solidarity, and loss into liberation. The Indian people, despite their limited resources, stood by the refugees, offering shelter, food, and medical aid. But it was the strength of the refugees themselves—their ability to endure, organise, fight back, and heal—that made the dream of Bangladesh possible.

These paintings are not just artistic expressions; they are witnesses of history, testimonies of the human spirit, and reminders of the price of freedom. Let us remember their journey, not just with sorrow, but with pride in their resilience and the birth of a nation born through sacrifice and unity.

Would you like me to draft an introduction or conclusion for your book based on these insights?