Author’s Note

This book is written with a sense of duty rather than dissent.

I have worn the uniform of the Bangladesh Army. I was commissioned into an institution that carries the legacy of sacrifice, discipline, and national service, forged in the crucible of the Liberation War of 1971. Like many officers of my generation, I was taught to revere the ideals of sovereignty, territorial integrity, and constitutional order. I was also trained to obey lawful authority and to subordinate personal ambition or political persuasion to the interests of the state.

It is precisely because of that training—and because of that oath—that this book exists.

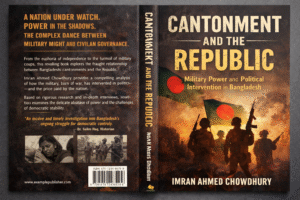

Cantonment and the Republic is not an indictment of the Bangladesh Army, nor is it an attempt to diminish its role in safeguarding the nation. It examines a historical pattern that has shaped the Bangladeshi state since 1975: the military’s recurring involvement in political power, whether through overt coups, counter-coups, indirect interventions, or prolonged shadow influence. This pattern has not only altered the course of civilian governance but also left a lasting imprint on the armed forces themselves.

The purpose of this book is to understand history honestly, without polemic and without fear.

In Bangladesh, discussions of military intervention are often reduced to binary narratives. One version portrays the armed forces as habitual usurpers of democratic authority. Another frames intervention as an unfortunate but necessary corrective to civilian incompetence or chaos. Both narratives are incomplete, and both do a disservice to history. Institutions are neither angels nor villains; doctrine, training, incentives, memory, and circumstance shape them. This book proceeds from that assumption.

As a former officer, I write from inside the culture I am analysing. I understand the Cantonments’ mindset, the pressures of hierarchy, the unspoken codes of loyalty, and the powerful moral language through which intervention has often been justified—“saving the nation,” “preventing collapse,” “restoring order.” I also understand how easily such language can propagate through the chain of command, particularly during periods of political uncertainty or institutional grievance. These insights are not offered as excuses, but as explanations.

At the same time, this book does not seek to absolve civilian political leadership of responsibility. Bangladesh’s post-independence political history is marked by intense polarisation, weak institutionalisation, personalised rule, and repeated failures to establish credible, peaceful transitions of power. Civilian governments have at times politicised state institutions, marginalised opposition, and undermined public trust. These failures created conditions in which military intervention appeared, to some, as a lesser evil. Recognising this reality is essential to any grave account of civil–military relations.

Yet recognition is not justification.

One of the central arguments of this book is that military intervention—whether brief or prolonged—ultimately weakened both democracy and the armed forces. Each intervention eroded constitutional norms, blurred professional boundaries, and embedded the military more deeply in political and economic networks, thereby complicating withdrawal. The result was not stability, but a cycle in which politics became militarised and the military became politicised.

This book also addresses a more uncomfortable question: inheritance. The Bangladesh Army did not emerge in a vacuum in 1971. Its early officer corps was trained mainly under Pakistan Army doctrine, command culture, and political assumptions formed between 1956 and 1971—a period in which military rule was normalised in Pakistan through the regimes of Ayub Khan and Yahya Khan. The influence of this legacy does not imply ideological loyalty to Pakistan, nor does it question the patriotism of Bengali officers. It does, however, raise legitimate questions about professional socialisation and institutional memory. These questions must be examined soberly, not defensively.

Foreign powers, too, appear in this narrative—not as omnipotent puppet masters, but as strategic actors whose preferences, tolerances, and silences sometimes shape outcomes. This book avoids conspiratorial determinism. It distinguishes between orchestration and acquiescence, between influence and control. Bangladesh’s political crises were primarily domestic in origin, even when external interests intersected with them.

Finally, a word on tone and intent.

This is not a memoir, though lived experience informs it. It is not a political manifesto, though it is grounded in constitutional principles. It is not an anti-military tract, though it is unafraid to name institutional failures. The aim is accountability through understanding, not blame through accusation.

If this book unsettles, it does so in the hope that honest history can strengthen, rather than weaken, the Republic. A professional military and a credible democracy are not opposing ideals. They are mutually dependent. Bangladesh’s challenge has never been to choose between them, but to reconcile them within a durable constitutional framework.

That reconciliation remains unfinished. This book attempts to explain why. Introduction

Cantonment, Power, and the Republic

Since the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on 15 August 1975, Bangladesh has experienced an extraordinary number of military interventions, attempted coups, counter-coups, mutinies, and politically motivated conspiracies originating within the cantonment. Some succeeded and reshaped the state. Many failed and disappeared into silence. Others never reached execution but left behind rumours, purges, mistrust, and institutional scars. Taken together, they form a pattern too persistent to be dismissed as a coincidence and too complex to be explained by a single cause.

This book begins from a simple but unsettling observation: in Bangladesh, political power has repeatedly been shaped not only in parliament or at the ballot box, but also—explicitly or implicitly—within the cantonment.

Understanding why this occurred requires moving beyond event-based narratives of coups and focusing instead on intervention as a political condition. In the Bangladeshi context, intervention has taken multiple forms: direct seizure of power; removal or installation of civilian leaders; imposition of emergency rule; behind-the-scenes pressure on elected governments; and prolonged influence over political outcomes without formal assumption of authority. These forms differ in method and visibility, but they share a common feature: the displacement or distortion of civilian political authority by military power rooted in the cantonment.

Why did such an intervention recur?

One explanation often offered is cultural—that the military, by nature, seeks political power. This explanation is both simplistic and ahistorical. Most professional armed forces across the world do not intervene in politics, even under extreme provocation. Another explanation places the burden entirely on civilian incompetence, portraying military intervention as a reluctant corrective to disorder or paralysis. This, too, is insufficient, as it ignores the institutional consequences of repeated military involvement and the consistent failure of such interventions to produce lasting democratic consolidation.

This book advances a more layered argument.

Military intervention in Bangladesh emerged from the interaction of several forces: an inherited military political culture shaped before 1971; weak post-independence civilian institutionalisation; unresolved legitimacy crises following liberation; factionalism within the officer corps; politicisation of promotions and grievances; and periods of foreign strategic tolerance. None of these factors alone caused intervention. Together, they created an environment in which intervention became conceivable, then acceptable, and eventually habitual within the cantonment’s political imagination.

The events of 1975 were decisive. The assassination of the country’s founding leader by serving officers shattered the post-Liberation moral consensus and removed the final taboo against military involvement in political outcomes. What followed was not a single coup, but a sequence of violent realignments—August, November, and the subsequent purges—that transformed the cantonment from a professional military space into an arena of political contestation. From that point onward, the question was no longer whether the military should intervene, but under what conditions and in whose favour.

Subsequent regimes institutionalised this reality in different ways. Military rulers sought legitimacy through constitutional engineering, the control of electoral processes, ideological realignment, and economic patronage. Civilian governments that followed often inherited a state already conditioned to cantonment influence and responded by politicising institutions rather than reforming them. The result was a cycle of mutual suspicion: politicians governed defensively, and the military retained a residual sense of guardianship over the Republic.

Crucially, this book distinguishes between coup-making and coup-thinking. Even as overt military takeovers declined after the 1990s, the underlying logic of intervention persisted. Governments anticipated military reaction. Political parties sought protection through alignment rather than legitimacy. The cantonment continued to function as an implicit reference point in moments of national crisis. Intervention thus evolved from an act into a condition—less visible, but no less consequential.

By 2007–2008, this evolution became explicit. The emergency regime did not emerge solely from tanks on the streets, but from a convergence of civilian paralysis, institutional fatigue, and elite consensus that democratic politics had become ungovernable. The fact that such a moment was again possible underscored how deeply the logic of cantonment intervention had become embedded in the state’s political consciousness.

This book does not argue that Bangladesh is uniquely prone to military intervention. Rather, it suggests that Bangladesh represents a case of an unfinished civil–military settlement. The Republic was born with exceptional moral legitimacy in 1971, but without fully developed institutions capable of managing political conflict, succession, and dissent. In that vacuum, the cantonment repeatedly appeared—sometimes by invitation, sometimes by default—as both actor and arbiter.

The central questions this book asks are therefore not accusatory, but structural:

- Why did military intervention appear rational to so many actors, civilian and military alike?

- How did inherited doctrines and professional socialisation shape officers attitudes toward political power?

- To what extent did civilian political failure invite intervention without justifying it?

- Why did intervention weaken, rather than stabilise, the Republic over time?

- And why have overt coups declined without a complete withdrawal of cantonment influence?

Cantonment and the Republic do not seek definitive answers to every question. It seeks clarity where myth has prevailed, nuance where slogans have dominated, and historical honesty where silence has endured. The story it tells is not one of heroes and villains, but of institutions struggling to define their boundaries within a young and contested state.

The Republic remains unfinished not because of the failure of a single institution, but because reconciliation between power and accountability has never been fully achieved. Understanding how the cantonment came to shape the Republic is a necessary step toward ensuring that it no longer does so.

The Political DNA of the Pakistan Army (1947–1971)

The political role of the military in Bangladesh cannot be understood as an aberration that emerged suddenly after independence, nor can it be reduced to individual ambition or episodic breakdowns of civilian authority. Its deeper roots lie in an inherited institutional culture shaped long before Bangladesh existed as a sovereign state. The Pakistan Army, from which the early Bangladesh Army partly emerged, was not merely a fighting force; it was an institution forged within insecurity, geopolitical anxiety, and a persistent belief that the survival of the state required guardianship beyond ordinary politics. This chapter explores how that belief took shape between 1947 and 1971, how it was reinforced by international alignments, and how its imprint carried forward—often unintentionally—into post-Liberation Bangladesh.

A state born in fear rather than settlement is the necessary starting point. Pakistan emerged from the Partition of British India not as a consolidated polity, but as a traumatised and unfinished state. The partition was violent, abrupt, and strategically unresolved. The new country inherited contested borders, particularly in Kashmir, a fractured economy, a weak political class, and a truncated administrative structure. Unlike India, which inherited the bulk of the colonial bureaucracy, industrial base, and political leadership, Pakistan began life with fewer institutional anchors and a persistent sense of vulnerability. From its earliest days, national survival—not constitutional development—became the overriding priority.

In this environment, the military assumed a significance that extended far beyond defence. The army was the most organised, disciplined, and centrally coordinated institution in the country. While civilian politics remained fragmented and constitution-making repeatedly delayed, the armed forces projected coherence and purpose. This imbalance was not inevitable, but it became structural. Over time, the military did not merely protect the state; it began to define it.

The colonial inheritance of authority further shaped this trajectory. The Pakistan Army was the direct successor of the British Indian Army, an institution trained not only to fight wars but to administer territory, suppress unrest, and enforce order across a colonial empire. British officers had ruled vast populations through military authority backed by bureaucratic control. Although the colonial army was formally subordinate to civilian rule in London, it exercised extraordinary autonomy on the ground. When this institutional culture was transferred to Pakistan, it arrived without the stabilising presence of a mature civilian political centre.

The result was paradoxical. An army trained to remain apolitical now operated within a state whose civilian institutions were weak, contested, and often paralysed. In such circumstances, the line between professional responsibility and political intervention became increasingly blurred. Military leaders began to view political instability not as a civilian problem to be endured, but as a national emergency to be resolved.

Early civilian failure and delayed constitutionalism accelerated this shift. Between 1947 and 1956, Pakistan experienced frequent changes of government, intense regional disputes, and prolonged constitutional uncertainty. Political parties were factionalised, leadership was thin, and governance often appeared improvised rather than institutional. The inability of civilian elites to deliver a stable constitutional order created a perception within the military that politicians were incapable of managing the state’s existential challenges.

This perception hardened into doctrine in 1958, when General Ayub Khan imposed Martial Law and assumed power. Ayub’s intervention marked a decisive break in Pakistan’s civil–military trajectory. Military rule was no longer exceptional; it was justified as necessary, modernising, and patriotic. Ayub presented the army as a rational, technocratic alternative to what he portrayed as corrupt and chaotic civilian politics. This narrative did not emerge spontaneously; it was carefully constructed and widely internalised within the officer corps.

From that point forward, military intervention acquired precedent. It became thinkable, defensible, and—crucially—successful. Power seized from civilians was retained, consolidated, and internationally recognised. For officers in training and service, this sent an unmistakable message: the army could rule, and rule effectively, when civilians failed.

The Cold War and Western strategic anxieties provided an external environment in which this internal logic flourished. In the early decades after the Second World War, Western powers—particularly the United States—viewed South Asia through the prism of global ideological competition. The Communist victory in China in 1949 profoundly altered Western strategic calculations. A powerful Communist state on Asia’s eastern flank raised fears of ideological contagion, regional instability, and Soviet expansion across Eurasia. At the same time, the emergence of India as a large, unified, and potentially influential democracy posed a different challenge: not ideological hostility, but strategic independence.

India, under Nehru, refused to align fully with either Cold War bloc. Its leadership of the Non-Aligned Movement signalled a determination to chart an autonomous path in global affairs. For Western policymakers, this independence was unsettling. While India was not Communist, it was also not reliably aligned with Western strategic priorities. Pakistan, by contrast, presented itself as a willing partner—security-focused, alliance-oriented, and eager for external support.

This convergence of interests led to Pakistan’s inclusion in Western-led military alliances, most notably SEATO and CENTO. These alliances were not explicitly designed for South Asia; they were components of a broader containment strategy aimed at limiting Soviet and Chinese influence across Asia and the Middle East. Pakistan’s participation was motivated by its desire for military assistance, international legitimacy, and strategic parity with India. For the West, Pakistan offered geographic position, ideological reliability, and a military willing to integrate into Western security frameworks.

SEATO and CENTO did not create Pakistan’s military dominance, but they undeniably reinforced it. Through these alliances, the Pakistan Army received modern equipment, training, and sustained engagement with Western militaries. Officers attended foreign courses, absorbed strategic doctrines, and developed an outward-looking professional identity. The army became the primary conduit between Pakistan and its most powerful international partners, particularly the United States.

This had profound internal consequences. Military prestige rose sharply, while civilian institutions lagged. Foreign policy and national security increasingly became military domains. Civilian leaders found themselves dependent on an army that not only commanded the armed forces but also controlled Pakistan’s most important external relations. Western governments, prioritising stability and alliance reliability over democratic development, often found military rule preferable to unpredictable civilian politics. This was not a conspiracy, but a pattern of strategic tolerance with lasting effects.

Within the officer corps, a guardian ethos took hold. Officers came to see themselves as custodians of national survival, endowed with a moral responsibility that transcended constitutional limits. This self-image was reinforced by training, institutional memory, and repeated political crises. The language of guardianship—saving the nation, restoring order, protecting ideology—became embedded in military discourse. It was not inherently sinister, but it was politically consequential.

Bengali officers serving within this system occupied an especially complex position. Professionally, they were trained in the same doctrines and exposed to the same assumptions about military responsibility and political order. Institutionally, however, they faced systemic discrimination. Despite constituting a majority of Pakistan’s population, Bengalis were underrepresented in senior military ranks and key command positions. Advancement was limited, postings were uneven, and trust was often withheld.

This dual experience produced a paradox. Bengali officers internalised the professional logic of military authority while simultaneously recognising the ethnic and political injustices embedded within the institution. They did not seek to emulate West Pakistani dominance, but they absorbed the belief that real power resided within the military hierarchy rather than civilian politics. For many, the army remained the only institution capable of decisive action, even as its leadership failed them.

The transition from Ayub to Yahya deepened the pattern. When Ayub Khan fell in 1969 amid widespread unrest, power did not revert to civilians; it transferred seamlessly to another general. This continuity reinforced a dangerous norm: that military leadership, not constitutional process, was the ultimate arbiter of political transition. Yahya Khan’s regime inherited both the authority and the assumptions of its predecessor, but lacked its discipline and restraint.

The catastrophic handling of the 1970 election and the subsequent military crackdown in East Pakistan marked the moral collapse of the Pakistan Army’s political project. The use of overwhelming force against civilian populations, the denial of electoral mandate, and the descent into genocide destroyed whatever legitimacy military rule still possessed. The 1971 war exposed the fatal flaw in the guardian doctrine: political problems cannot be solved through coercion without destroying the state itself.

For Bengali officers and soldiers, 1971 was transformative. It shattered any residual faith in Pakistan’s political order and compelled a fundamental reassessment of loyalty, authority, and legitimacy. Many joined the Liberation War; others were imprisoned, sidelined, or traumatised. The creation of Bangladesh represented a decisive rejection of Pakistani domination—but it did not automatically erase decades of professional socialisation.

Inheritance, not intention, explains continuity. The Bangladesh Army emerged from the Liberation War with extraordinary moral legitimacy, rooted in resistance and sacrifice. Yet its early officer corps carried with it an institutional memory shaped by Pakistan’s military culture. This inheritance did not predetermine future intervention, but it conditioned how power was imagined, justified, and contested. The cantonment did not enter Bangladeshi politics as a conspirator; it entered as an institution shaped by precedent, insecurity, and unexamined assumptions about responsibility.

Western alliances, Cold War anxieties, and regional rivalries did not dictate this outcome, but they influenced the environment in which it unfolded. Fear of Communist expansion, uncertainty about India’s strategic autonomy, and the prioritisation of stability over democratic experimentation all contributed to a regional order in which military institutions were empowered more rapidly than civilian ones. The consequences of that imbalance would echo far beyond 1971.

The story that follows in this book is not one of betrayal, but of unfinished settlement. The political DNA formed between 1947 and 1971 did not compel Bangladesh’s later crises, but it shaped the conditions under which they became possible. Understanding that inheritance is essential—not to assign blame, but to explain why the cantonment would later emerge as a recurring site of political power in a Republic still struggling to reconcile authority with accountability.

Liberation, Authority, and the Unfinished Civilian Settlement (1971–1975)

Bangladesh was not born from negotiation. It was born from defiance, blood, and an extraordinary convergence of courage across ranks, professions, and social classes. Its independence was not gifted by history; it was seized by men and women who chose resistance when submission appeared safer, and sacrifice when survival demanded silence. Any serious examination of civil–military relations in Bangladesh must therefore begin with an unambiguous truth: the Liberation War of 1971 was not merely a popular uprising, nor solely a military rebellion. It was a national war of liberation, forged through the combined heroism of defecting soldiers, paramilitary forces, police, civilian fighters, and an unarmed population that refused to surrender its political mandate.

At the centre of this struggle stood a relatively small but decisive cadre: approximately 175 to 200 Bengali commissioned officers of the Pakistan Army who deserted, defected, or escaped to organise armed resistance. Their role was disproportionate to their number. They provided not only military leadership but coherence—transforming scattered acts of rebellion into a structured war effort. Without them, courage might still have burned brightly, but victory would have been far less certain.

The moment of rupture came swiftly and brutally. On the night of 25 March 1971, the Pakistan Army launched a coordinated campaign of terror against the civilian population of East Pakistan. What followed was not counter-insurgency but annihilation: universities targeted, neighbourhoods razed, political leaders arrested or killed, civilians massacred on ethnic and political grounds. For Bengali soldiers serving within the Pakistan Army, the events of that night shattered any remaining illusion of shared national purpose. The state they had sworn to serve had turned its guns on its own people.

For many, the choice that followed was neither abstract nor ideological. It was immediate and moral. To remain within the ranks was to become complicit. To desert was to risk death—not only from the enemy but from uncertainty itself. Yet desert they did, often in isolation, without orders, without assurances, and without any guarantee that resistance would succeed. This decision—made individually, repeatedly, and under extreme danger—constituted one of the most consequential acts of collective moral courage in South Asian military history.

Alongside these officers stood the East Pakistan Rifles (EPR), whose role in the early days of the war was both heroic and tragic. As a paramilitary force with deep roots in local communities, the EPR was uniquely positioned to resist. In multiple locations, EPR units revolted almost instinctively, engaging better-equipped Pakistani forces despite limited ammunition and unclear prospects. Their resistance delayed the consolidation of Pakistani control, bought time for political leadership to regroup, and inspired wider rebellion.

The cost was devastating. Many EPR personnel were overrun, executed, or annihilated in place. Entire units were destroyed. Yet their sacrifice was not in vain. In resisting when resistance seemed futile, they transformed despair into possibility. The EPR’s early stand remains one of the unsung pillars of the Liberation War.

The Police, too, must be acknowledged not as passive victims but as active participants. Often overlooked in military histories, Bengali police units were among the first to resist Pakistani forces, particularly in urban centres. Armed with little more than service rifles and local knowledge, they confronted professional troops in unequal engagements. Many were killed. Many more joined the resistance, bringing organisational experience, intelligence, and legitimacy to the emerging struggle.

Beyond uniformed forces lay the vast, unarmed mass of the population—the farmers, students, labourers, professionals, and villagers who constituted the backbone of the Mukti Bahini. Their contribution defies quantification. They sheltered fighters, carried messages, gathered intelligence, sabotaged supply lines, and endured collective punishment with remarkable resilience. Villages were burned, families destroyed, women violated, yet the will to resist did not collapse. The Liberation War was sustained as much by civilian endurance as by military action.

Leadership, however, remained indispensable. Courage alone does not win wars; organisation does. The roughly 175–200 Bengali commissioned officers who emerged as leaders during the war carried a burden far heavier than rank would suggest. Many were young—some barely beyond junior command—but they were forced to assume strategic responsibility almost overnight. They organised training camps, coordinated operations across sectors, liaised with political leadership, and imposed discipline on forces drawn from disparate backgrounds.

These officers did not command a conventional army. They led an improvised, evolving force composed of regular soldiers, paramilitaries, police, and civilians. They operated with scarce resources, uncertain intelligence, and a constant threat of infiltration. Yet they succeeded in creating a functional command structure divided into sectors, each with operational coherence. This achievement alone marks the Liberation War as not merely a rebellion, but a professionally guided war of independence.

The victory of December 1971 thus conferred upon the armed forces of Bangladesh a unique moral authority. Unlike many post-colonial armies, the Bangladesh Army was not born as an inheritor of colonial coercion or post-independence repression. It was born of resistance, sacrifice, and popular legitimacy. Its officers and soldiers were not strangers to the people; they were their sons, brothers, and neighbours. Few institutions in Bangladesh would ever command such unquestioned respect again.

Yet victory carries its own burdens. The end of the war did not resolve the fundamental question of authority; it merely deferred it. Bangladesh emerged from 1971 with overwhelming moral clarity but fragile institutional foundations. The state had been liberated, but not yet fully constituted. Civilian political authority, though legitimate in principle, faced immense practical challenges: the reconstruction of a devastated economy, the rehabilitation of millions of refugees, the restoration of law and order, and the integration of diverse armed groups into a unified national framework.

The armed forces, for their part, faced an equally complex transition. A wartime command structure had to be transformed into a peacetime professional army. Guerrilla leaders had to become administrators. Revolutionary legitimacy had to give way to constitutional subordination. This transition is difficult for any post-liberation force; in Bangladesh, it was compounded by scarcity, political turbulence, and unresolved ideological divisions.

The early years of independence were therefore marked by ambiguity rather than consolidation. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, as the undisputed leader of the independence movement, possessed unparalleled popular legitimacy. Yet his government inherited a shattered state apparatus and an economy in ruins. Civilian institutions were weak, inexperienced, and often overwhelmed. In this environment, reliance on security forces for internal stability increased, even as formal civilian supremacy was asserted.

This tension was not unique to Bangladesh, but its context was distinctive. The same officers who had liberated the country now found themselves navigating a political order that was still taking shape. They were revered as heroes, yet expected to withdraw quietly from political relevance. The boundaries between respect, influence, and authority were not clearly drawn. No comprehensive civil–military settlement was negotiated, codified, or internalised.

Compounding this uncertainty was the fragmentation of armed legitimacy. The Liberation War had mobilised multiple forces with overlapping claims to contribution and sacrifice. Integrating these forces into a single, disciplined military under civilian command required careful management, political sensitivity, and institutional foresight. Where this process faltered, grievances festered—over rank, recognition, promotion, and post-war status.

At the same time, the broader political environment grew increasingly strained. Economic hardship, famine, administrative weakness, and political polarisation eroded public confidence. Opposition movements intensified. The government responded with centralisation of power, emergency measures, and restrictions on political pluralism. Each step, however justified in intent, narrowed the space for consensus and deepened mutual suspicion between institutions.

This was the essence of the unfinished civilian settlement. Bangladesh had achieved independence without fully resolving how authority would be shared, limited, and transferred within a constitutional framework. The relationship between the cantonment and the Republic remained undefined—not adversarial, but unsettled. The army did not seek power in these early years, but neither was it fully insulated from politics. Civilian leadership asserted supremacy, but without embedding it in durable institutional practice.

The tragedy of this period lies not in betrayal, but in missed opportunity. The moral capital of 1971 was immense. The legitimacy of civilian leadership was real. The professionalism and patriotism of the armed forces were unquestioned. Yet the structures needed to reconcile these forces—to ensure that heroism translated into stable constitutional order—were not fully constructed.

By 1975, the cumulative weight of political unrest, economic distress, and institutional ambiguity would prove fatal to this fragile equilibrium. The violent rupture that followed did not arise from the Liberation War’s legacy, but from the failure to complete its political promise.

This chapter insists on a central truth that must never be diluted: the Bangladesh Army’s origins lie in heroism, sacrifice, and popular resistance. Any later intervention must be judged against that standard—not to condemn the institution, but to understand how far the Republic drifted from the clarity of its founding moment.

The story that follows is not a negation of 1971, but its unresolved aftermath. Liberation created a nation. Settlement was left unfinished.