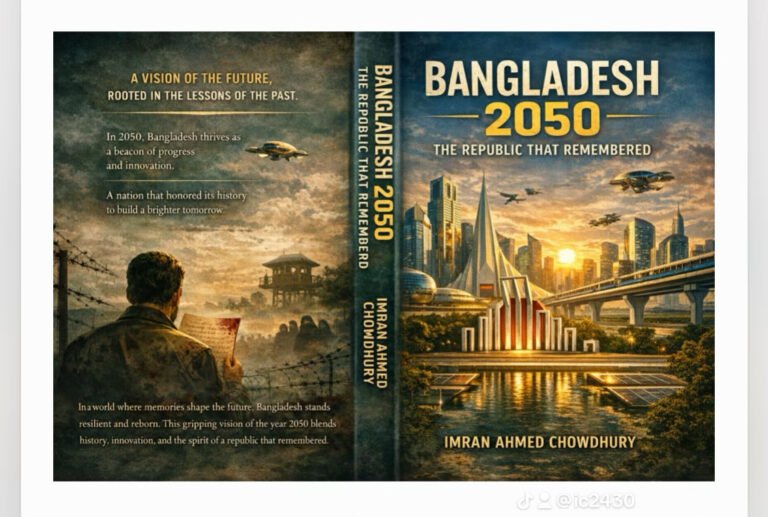

A new Book

by

Imran Ahmed Chowdhury

Introduction: On Order, Memory, and the Republic

By the middle of the twenty-first century, Bangladesh had achieved what earlier generations had sought with urgency and exhaustion: stability.

There were no tanks on the streets. No emergency decrees. No sudden disappearances that could not be explained administratively. The state functioned. Services were delivered. Elections were held. The economy grew steadily, if unevenly. For many citizens, the Republic appeared to have matured.

Yet something essential had shifted—not abruptly, but quietly.

Conflict did not vanish; it was reclassified. Dissent was not criminalised; it was diagnosed. Faith was not suppressed; it was organised. History was not destroyed; it was curated. What remained was a republic that no longer argued with itself, because it had learned to speak in a single voice.

This book takes place within that voice.

The narrative that follows is not concerned with heroes or villains. It follows functionaries, auditors, officials, and citizens who believe they are doing their duty. Their world is not brutal. It is procedural. Decisions are made by frameworks. Judgments are issued by indices. Morality is certified.

In this Republic, the past exists—but only in approved forms. The Liberation War is remembered, but without ambiguity. Faith is respected, but without interpretation. Freedom is acknowledged, but without risk.

The central question is not whether this system is evil. It is whether it is complete. Whether a nation can be fully governed without allowing disorder, disagreement, or memory to intrude.

As you read, it may be tempting to search for parallels, to identify echoes of familiar debates and recognisable anxieties. That impulse is natural. But this book does not ask to be read as commentary on present politics. It asks to be read as a study of possibility.

Every society chooses what it fears most. Some fear chaos. Others fear memory. The Republic described here chose the latter—and built its future accordingly.

What follows is not a forecast. It is a mirror, angled slightly toward tomorrow.

Why This Book Was Written

This book is a work of speculative fiction. It is not a prediction, nor is it a prophecy. It is an exercise in imagination grounded in history, observation, and concern.

Bangladesh was born from a rare moral clarity. Few nations emerge from such profound sacrifice with a shared sense of purpose as strong as that which shaped the country in 1971. Yet history has shown that moral origins do not guarantee moral continuity. States, like individuals, can forget who they were—especially when power becomes fearful of memory.

Over the past decades, Bangladesh has experienced cycles of order and disorder, progress and regression, belief and coercion. Each phase has been accompanied by a promise of stability. Each has also demanded a price—sometimes paid in silence, sometimes in fear, and sometimes in forgetting.

This book asks a simple but unsettling question: What if stability becomes the highest political virtue? What happens when order is valued above liberty, compliance above conscience, and harmony above truth? What if a nation reaches a future where conflict has been solved—not through justice, but through erasure?

The Bangladesh imagined in this novel is not born of sudden catastrophe. It arrives gradually, through policies that appear reasonable, reforms that promise efficiency, and moral arguments that seem protective rather than oppressive. Surveillance replaces suspicion. Algorithms replace debate. Faith is not abolished; it is regulated. History is not denied; it is edited.

This is not a book about villains. It is a book about systems—how they grow, how they justify themselves, and how ordinary people learn to live within them. The most enduring forms of control are not those imposed by violence, but those accepted as normal.

The choice to set this novel in 2050 is deliberate. It is far enough to allow imagination, yet close enough to remain uncomfortable. The characters in this book do not experience their world as dystopian. They experience it as orderly, predictable, and safe. That is precisely the danger.

If this book unsettles, it is because it touches questions that remain unresolved: the role of faith in governance, the management of dissent, the rewriting of national memory, and the quiet transformation of citizenship into obedience. These are not uniquely Bangladeshi questions. They are universal. Bangladesh merely provides the setting through which they are examined.

This novel does not offer solutions. It offers a warning—expressed through story rather than argument. The hope, if any, lies not in revolution, but in remembrance. In the belief that history, once truly remembered, resists captivity.

This book is written for readers who understand that the future is never built in a single moment, but assembled patiently, choice by choice, compromise by compromise.