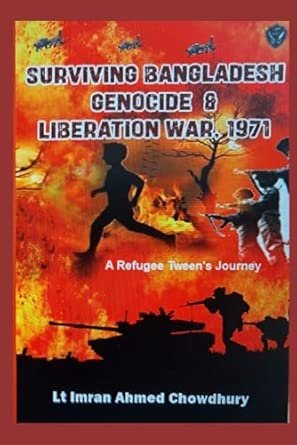

In 1971, the soil of Bengal was soaked in blood, sacrifice, and resilience. Bangladesh emerged as an independent state after a nine-month war in which an estimated three million people were killed, hundreds of thousands of women were raped, and ten million people took refuge in India (Rummel, Death by Government, 1997). For those of us who lived through that war, the memories are not abstract—they are searing, personal, and deeply ingrained in our lives.

I was one of those who fled to India as a child refugee. My father, a company commander of the East Pakistan Rifles (EPR), led one of the earliest revolts against the Pakistan Army’s genocidal campaign on 27 March 1971 in Sylhet. My elder brother, barely seventeen, joined as a guerrilla freedom fighter in the countryside. On Eid day, he was captured and brutally murdered by the Pakistan Army, his body dumped by the banks of the Titas River in Brahmanbaria. His martyrdom is etched into my memory as a cruel reminder of what freedom costs us.

Yet today, over half a century later, I watch in despair as the ethos and aspirations of that liberation war are betrayed. The very regime that governs Bangladesh now appears to be cosying up with Pakistan—the same perpetrators of genocide—and their deep state allies, erasing the sacrifices that birthed this nation.

1971: A Struggle for Existence

The war was not simply a conflict over political autonomy. It was a struggle for existence. When Operation Searchlight was unleashed on 25 March 1971, it was nothing short of genocide. The New York Times reported the next day: “The Pakistani Army has launched a full-scale military operation in East Pakistan, killing students, civilians, and even patients in hospitals” (NYT, 27 March 1971).

Archer K. Blood, the then U.S. Consul General in Dhaka, in his famous “Blood Telegram,” wrote: “Within the last 24 hours, we have reports that several thousand people have been killed, including students in Dhaka University… It is, in short, a reign of terror by the Pak military.”

For Bengalis, the war was about securing dignity, justice, and the right to live without subjugation. The aspiration was profound yet straightforward: a secular, democratic, and sovereign Bangladesh where the spirit of the martyrs would be honoured.

The Betrayal of Liberation Ideals

But the dream of 1971 was quickly clouded by political conspiracies, coups, assassinations, and authoritarianism. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the Father of the Nation, was assassinated in 1975 along with most of his family. The military regimes that followed—first under General Ziaur Rahman and later under General Hussain Muhammad Ershad—systematically rehabilitated war criminals, collaborators, and those who had sided with Pakistan in 1971.

Dr Ali Riaz, a distinguished scholar of South Asian politics, notes, “The post-1975 regimes not only abandoned the spirit of secularism and inclusivity but actively rehabilitated the political and religious forces opposed to the independence of Bangladesh” (Islamist Militancy in Bangladesh, 2008).

The Jamaat-e-Islami, banned for its collaboration with Pakistan during the war, was legitimised and allowed into mainstream politics. War criminals occupied parliament. The Constitution itself was distorted to erase secularism and insert communal rhetoric.

This was not just a political compromise; it was a betrayal. It was the slow undoing of the very ideals for which millions died.

The Present Regime and Pakistan: A Dangerous Dance

Today, Bangladesh stands at a crossroads once again. Despite decades of rhetoric against 1971 collaborators, the current regime’s actions tell a different story. While ordinary citizens carry deep scars of 1971, the political leadership is increasingly seen to be softening towards Pakistan.

Recent diplomatic overtures, trade talks, and intelligence back-channel contacts suggest that Dhaka is ready to normalise relations with Islamabad beyond pragmatic diplomacy. However, this is not merely a matter of foreign policy—it cuts to the heart of Bangladesh’s historical consciousness. To reconcile with a state that has never apologised for its genocide, never repatriated its war criminals, and never compensated its victims is to dishonour the martyrs of 1971.

As Dr Sarmila Bose controversially wrote in Dead Reckoning (2011)—though widely criticised—Pakistan has never accepted responsibility for its crimes. Instead, its military establishment continues to downplay or deny the genocide. For Bangladesh to now extend an open hand without demanding accountability is nothing short of erasing history.

A Nation at Risk of Becoming a Failed State

Bangladesh is not only at risk of forgetting its history; it is also at risk of becoming a failed state. Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index consistently ranks Bangladesh among the most corrupt countries in South Asia. Civil society voices are stifled, opposition politics are crippled, and the press is increasingly under surveillance and censorship.

Nobel laureate Amartya Sen once remarked, “Democracy is not just about elections; it is about freedom of thought, expression, and dissent” (The Argumentative Indian, 2005). In Bangladesh, these freedoms are evaporating. Elections are stage-managed. State institutions—from the judiciary to the bureaucracy—are instruments of partisan control.

The international community, including the U.S. State Department and the European Union, has raised concerns about democratic backsliding in Bangladesh. The Economist bluntly described the situation: “Bangladesh has turned into an electoral autocracy” (The Economist, January 2024).

These are not signs of a thriving nation. They are symptoms of a failing state—one that risks collapsing under the weight of its own contradictions.

Personal Pain, National Warning

For me, this is not just a matter of political analysis—it is deeply personal. I carry the memory of a father who led men into revolt against the Pakistan Army’s genocide. I have the grief of a brother murdered as a teenage guerrilla. I carry the trauma of refugee camps in India. These are not memories to be bartered away in diplomatic games.

When I see today’s rulers shaking hands with Pakistan, inviting their envoys, or overlooking their crimes, I feel as though my brother’s body is being dumped into the Titas River all over again. It is as if the martyrs are being killed once more—not by bullets this time, but by silence, opportunism, and betrayal.

The Call of Conscience

Bangladesh must remember that nations are not destroyed only by external enemies but also by internal betrayal. As George Santayana warned, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

If Bangladesh forgets 1971, if it erases its martyrs, if it allows collaborators and perpetrators to re-enter through the back door, then it will not just lose its history—it will lose its soul.

Our martyrs did not die so that a new elite could turn Bangladesh into a client state of Pakistan, China, or any other power. They died so that the people of Bengal could breathe free, live with dignity, and stand tall in the community of nations.

It is the duty of every Bangladeshi—especially those of us who bore the wounds of 1971—to speak out. To remind the young that freedom was not free. To resist those who trade away sovereignty for power. To insist that Pakistan must first apologise, acknowledge genocide, and repent before it can ever be treated as a partner.

Conclusion: Defend the Dream of 1971

Fifty-four years have passed since independence. But the war is not over. The battlefield has shifted—from the killing fields of 1971 to the corridors of politics, diplomacy, and memory. The question now is not whether Bangladesh can survive external threats, but whether it can survive its own betrayal.

The dream of 1971 is fragile but not dead. It lives in the stories of refugees, in the tears of mothers, in the blood of martyrs by the Titas River, and in the defiance of every Bengali who still believes in freedom.

Bangladesh must choose: to honour that dream or to betray it. The stakes are nothing less than the soul of the nation.

✍️ By Imran Ahmed Chowdhury BEM

Refugee of 1971, son of an East Pakistan Rifles company commander, and brother of a martyred teenage guerrilla.