In the soft amber light of memory, some journeys never fade. Among the most vivid recollections of my adolescent days in then East Pakistan are those long, leisurely voyages by steamer and launch—floating through the winding rivers that stitched together Dhaka, Khulna, Narayanganj, and the enchanting forest-fringed routes to Bagerhat and Kaligong. These were not just modes of travel. They were experiences, meditative and immersive, breathing with the rhythm of the land and water.

The journey would often begin at Sadarghat, Dhaka, a place bustling with the noise and aroma of the river port, the chaos of passengers, and the scent of river water mixed with the aroma of dried fish and tea. From here, the steamer would slowly push off, its tall chimney puffing rhythmic clouds of smoke like a restless genie freed from an ancient brass lamp. As the launch glided into the broader embrace of the rivers, the clatter and commotion of the city would recede, replaced by the gentle lapping of water against the hull.

Traveling towards Khulna felt like drifting into a dream. The steamer cruised through tidal rivers whose moods changed with every hour. At one moment, the vessel rode on water nearly brimming over the banks, hiding the muddy shores like a secret. And then, like a magician’s sleight of hand, the tide would retreat, revealing sloped, muddy banks scarred with the footprints of crabs and the curved trails of slithering eels. The low tide unveiled a different world, a land of stillness where mangrove roots clawed the air and sandbanks shimmered under the sun.

It was during these tide transitions that the secrets of the Sundarbans would sometimes reveal themselves. I remember the breathless moment when, from the deck chair, I saw a spotted deer emerge from the treeline. Its gait was hesitant, cautious. It paused at the river’s edge, nostrils flaring, ears twitching. Every movement was measured, an instinctive dance between thirst and fear. Somewhere behind that green curtain of golpata, in the dense foliage, the silent watcher—the Royal Bengal Tiger—might have been tracking its prey. The thought thrilled me and sent a shiver down my spine, even as the humid breeze brushed against my face.

The steamer, unhurried and graceful, carved its path through the meandering rivers. The waters, often dark and mysterious, would glisten in the sunlight with the reflections of overhanging branches, dappling the surface with patterns of green and gold. As we approached Khulna or meandered further into the forest-bordered stretches near Bagerhat and Kaligong, the waterway became a tapestry of life. Small canoes darted past, their fishermen casting nets with practiced ease, while children waved from distant huts built on stilts, their laughter echoing faintly across the water.

There was something mesmerizing about being on the deck during these voyages. I remember those deck chairs—metal-framed with woven seats, rocking gently with the movement of the vessel. Sitting there, I felt detached from the world, yet deeply connected to it. The smoke from the steamer’s chimney would rise and curl into the sky, sometimes catching the breeze and swirling back over us like a blessing. The scent of oil, coal, and river water mixed in the air. Occasionally, a vendor from the lower deck would climb up with tea in earthen cups or boiled eggs with a pinch of salt and chili—simple delights that tasted of freedom and open skies.

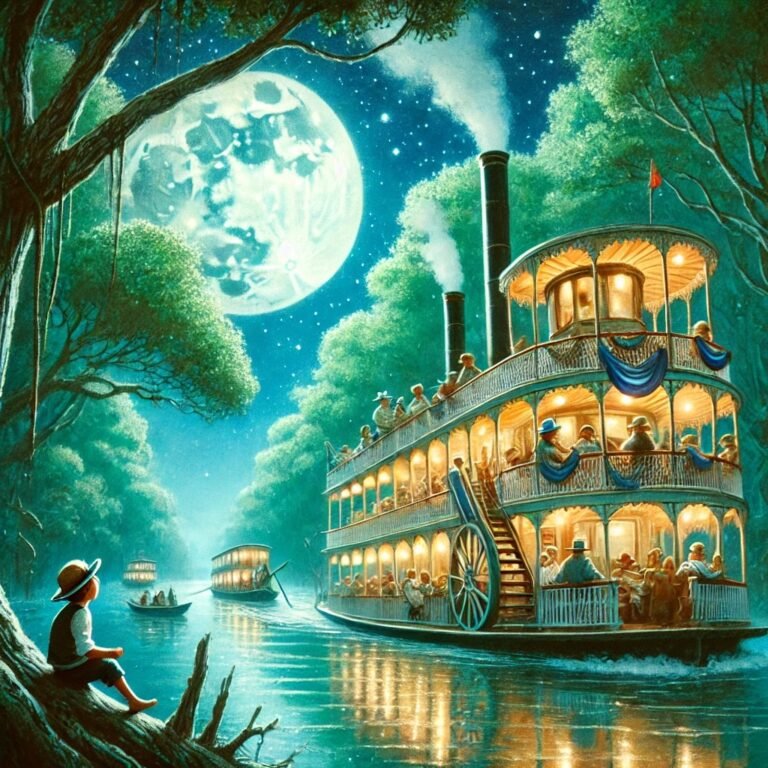

Nightfall brought with it a kind of magic that only river journeys can offer. As dusk descended, the forests on either side darkened into silhouettes. The sounds shifted—frogs began their chorus, crickets chirped in waves, and the distant call of a bird occasionally pierced the hush. The moon would rise like a guardian in the sky, its silvery light painting a path on the rippling river. The waves behind the steamer, churned by its movement, shimmered like liquid glass, each ripple catching the moonlight and dancing with it.

Far in the horizon, we would sometimes see a lonely fishing boat, gently swaying with the current. A lantern would hang at its bow, flickering like a heartbeat in the dark, a solitary dot of life in a sea of silence. That sight—a small boat, a single light—would stir emotions I couldn’t quite name at the time. Looking back, perhaps it was a sense of oneness with the universe, the realization of how vast the world was, and yet how intimately it spoke to the soul.

The route from Khulna to Narayanganj, and then onward to places like Bagerhat and Kaligong, were not merely geographical connections—they were spiritual transitions. These steamer journeys carried more than people and goods. They transported stories, dreams, and emotions. They allowed you to float not just over water, but also within yourself.

As a boy, I didn’t realize that I was storing away scenes and scents and sounds in some sacred vault of memory. But today, decades later, I find myself returning to those journeys whenever life feels too fast, too artificial. The muddy banks, the shy deer, the prowling tiger, the shimmering wake under moonlight, and that ever-burning lantern in a faraway boat—they remind me of who I was and what it meant to truly observe the world.

Perhaps those slow, steamer voyages taught me the essence of time: that not everything must be hurried; that beauty is found in the in-between; that silence can be the loudest conversation with nature.

In the heart of what is now Bangladesh, those rivers still flow. Steamers may have grown fewer, and the golpata forests may have thinned, but I know that if I were to close my eyes and listen carefully, I could still hear the distant chug of an old launch, its chimney puffing into the sky, carrying some wide-eyed boy into the wilderness of wonder once more.