Honouring My Brother, the Fallen Freedom Fighter

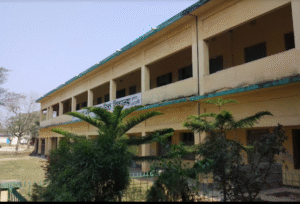

Building a school in my village was born out of grief and hope. It was my way of preserving the memory of my elder brother, a young man who gave his life for Bangladesh’s independence.

His sacrifice was among many—thousands of young men and women left their homes, families, and dreams behind to fight for a free Bangladesh. But like so many of them, his name was lost in the chaos of war, buried in the pages of history. There were no grand memorials, state recognition, or records of his heroism.

That didn’t sit well with my family. My brother’s name, Shaheed Babul High School, and the sacrifices of many like him deserve to be remembered.

And what better way to honor his legacy than by investing in education—the very thing that war had denied him?

We wanted to build a school in his name, where the children of our village—especially those from poor families—could have the opportunity to learn, grow, and build a future that he never got to see.

But the journey to building that school was anything but easy.

The Challenges of Establishing an Educational Institution

The First Hurdle: Convincing the Community

When my father first spoke to me, as a 12-year-old, I supported my father straight away. The idea of building a school was brought up, and many people dismissed it as a dream—a noble one, but unrealistic.

At the time, our village, like many rural areas in Bangladesh, was struggling to rebuild after the war. People were more concerned with survival—finding food, securing shelter, and earning enough money to support their families.

When my father spoke to the village elders about the need for a school, we were met with skepticism.

-

“Education is important, but who will fund it?”

-

“How will we build a school when people don’t even have proper homes?”

-

“It’s a good idea, but it’s impossible.”

But I refused to believe that it was impossible.

I knew it would never come if we waited for the right time. If we waited until every problem was solved, the children of our village would grow up without an education—just like many generations before them.

Funding the Project: A Daunting Task

My father told me that after the devastating war, no crops on the land, all the savings in the banks were gone, and everything tangible was burned or looted during the war. He suggested that I start fundraising from people.

I started networking with my classmates in the school. Once I had convinced some friends and community members that the school was necessary, the next challenge was funding.

Building a school required money—land, materials, teachers, books, furniture—and I had none.

I knew that if we. Wanted to make this dream a reality, but I would have to raise the funds myself.

I started small.

I knocked on doors, explaining my vision to anyone who would listen. I asked local businessmen, community leaders, and philanthropists for donations. Some were generous; others were doubtful.

To raise money, I took on extra jobs—I worked tirelessly, saving every penny I could.

However, the most significant turning point came when I contacted the BDR ( Bangladesh Rifles ), which serves people and their families.

Many Bangladeshis who had moved abroad—especially those living in the UK from Sylhet—still had a deep connection to their homeland. They wanted to give back, but they didn’t always know how. When I shared my plan, I found many people willing to help.

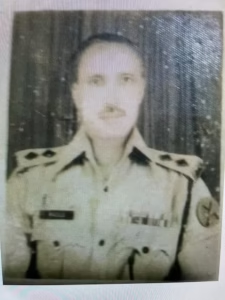

In Chudanga, where my father was posted as the Wing Commander of BDR in 1973, the generosity of the people to give donations was unbelievable; I owe so much humble gratitude and owe them a great deal of homage.

Little by little, donations started to come in. Some gave money; others donated books, school supplies, and materials. No matter how small, every single contribution brought us one step closer to building the school.

Navigating Bureaucracy and Red Tape

Like in many developing countries, bureaucracy can be one of Bangladesh’s most significant barriers to progress.

My father quickly learned that getting permission to build a school was a long and frustrating.

Legal requirements, permits, and government approvals had to be secured.

Officials demanded endless paperwork, and sometimes things stalled because I refused to pay bribes.

There were moments of deep frustration when we wondered if this fight was even worth it. But every time we felt discouraged, I thought of my brother’s sacrifice. Father and the family thought of the children who would grow up without an education if we gave up.

And so, we kept going.

After months of persistence, meeting with officials, filling out forms, and waiting in endless queues, we finally got the necessary approvals.

It was one of the most significant victories of my family’s life.

Shaheed Babul Chowdhury: The Young Flame of Freedom

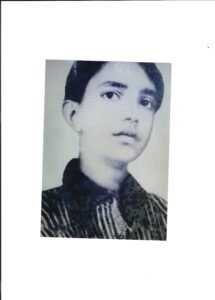

In the tumultuous pages of Bangladesh’s struggle for independence, many names are etched into the consciousness of a nation—a few celebrated widely and many unsung. Among these brave souls stands a 17-year-old guerrilla fighter, Shaheed Babul Chowdhury, whose youthful passion, unyielding spirit, and ultimate sacrifice have become part of a legacy that continues to inspire generations.

Born into a time when East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) was simmering under the weight of political neglect, economic disparity, and cultural alienation imposed by West Pakistan, Babul Chowdhury grew up in a household that understood the tides of history. His father, a distinguished officer in the East Pakistan Rifles, would later ignite the first flame of rebellion in the Sylhet region during the war. This sense of duty and resistance was not just inherited—it was lived, breathed, and ultimately, given up in martyrdom by young Babul.

The Backdrop of a Nation’s Struggle

To understand Babul Chowdhury’s place in history, one must journey through the annals of the 1971 Liberation War—a movement born out of the denial of democratic rights, linguistic suppression, and brutal military oppression.

The seeds were sown in 1947 when British India was partitioned to create Pakistan, a country divided into two wings—East and West—separated by more than a thousand miles of Indian territory. Despite East Pakistan housing the majority population, the reins of power were firmly held in the West. Economic disparities widened. Bengali, the mother tongue of the people of the East, was undermined in favour of Urdu. These injustices culminated in a political flashpoint in 1970, when the Awami League, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, won a landslide victory in national elections—only to be denied the right to govern.

On March 25, 1971, the Pakistan Army launched Operation Searchlight, a genocidal military crackdown on unarmed civilians, students, and political activists in Dhaka and across East Pakistan. The Bangladesh Liberation War had begun, and with it, a tide of resistance that spread from trained soldiers to spirited teenagers like Babul Chowdhury.

The Path of a Guerrilla

At the age of just 17, Babul Chowdhury could have chosen safety. Instead, he chose sacrifice. Inspired by the call for independence and driven by an unshakable sense of justice, Babul joined the Mukti Bahini—the Freedom Fighters of Bangladesh. Operating in small guerrilla cells, these brave young men and women engaged in acts of sabotage, intelligence gathering, ambushes, and direct attacks against the occupying Pakistani forces and their local collaborators, the Razakars and Al-Badr.

It was in the region of Brahmanbaria, a strategically important district in the eastern theatre of the war, that Babul’s commitment to the cause deepened. His courage was not marked by reckless bravado but by a fierce determination to rid his motherland of foreign control and systemic cruelty. For months, he and his fellow fighters waged a silent war in the shadows—dodging death daily, driven by a singular dream: Shadhin Bangladesh.

But in war, especially one where brutality knows no bounds, courage is often met with cruelty.

Captured and Martyred

On 21st November 1971, with victory for the Mukti Bahini and the Indian allied forces drawing near, the Pakistan Army and their collaborators intensified their efforts to silence all opposition. During a covert mission in Brahmanbaria, Babul was captured. What followed was a harrowing chapter of inhuman torture and interrogation.

Stripped of his dignity but never his resolve, Babul endured pain that would break most adults, let alone a teenager. He never revealed the identities of his comrades nor betrayed the cause. For that unwavering defiance, the Pakistani military made him pay the ultimate price.

He was executed—martyred—on that cold November day. Just 17 years old.

News of his death sent ripples through the resistance. His sacrifice became a symbol—of the young generation’s unflinching commitment to freedom, of the blood-soaked birth of a nation that would soon rise from the ashes.

A Name Among Millions, A Legacy Above Many

Shaheed Babul Chowdhury is one of the countless young men and women who perished during the nine months of the Liberation War. According to various estimates, more than three million Bengalis were killed, and over ten million fled to India as refugees. Hundreds of thousands of women were subjected to rape and torture, while an entire generation bore the scars of genocide.

Yet amidst this dark and tragic history, Babul’s story glows with a quiet light—because it speaks of hope, conviction, and the timeless power of youth. He did not live to see the red and green flag of Bangladesh hoisted in victory on 16th December 1971, but he helped weave that flag with his blood.

Today, Bangladesh stands as a free nation, thriving in many ways, struggling in others. But its independence came not from diplomacy or political manoeuvres—it came from the barrels of freedom fighters’ guns, from the silent endurance of its people, and from the selfless martyrdom of boys like Babul Chowdhury.

Remembering the Martyrs, Rekindling the Flame

Babul Chowdhury

As time passes, memory fades. The generation that bled for Bangladesh grows older, and the risk of their stories being lost looms large. That is why it is essential, even sacred, to preserve the legacy of fighters like Babul—not just in state monuments or school textbooks but in the hearts and minds of every Bangladeshi.

We must ask ourselves: what does it mean to inherit freedom that came at the cost of so many lives? What would Babul say to today’s youth? Would he feel pride in our progress or dismay at the corruption, injustice, and indifference that sometimes plague the ideals he fought for?

The answer lies in how we remember him—not as just a martyr but as a mirror. A mirror that reflects courage, resilience, and sacrifice. A mirror that dares us to ask: what are we doing to honour their sacrifice?

Final Thoughts

Shaheed Babul Chowdhury was not a general or a politician. He did not write manifestos or lead battalions. He was simply a boy who loved his land, believed in freedom, and gave his life so others could live with dignity. Like thousands of others, his story is not just history—it is a call to conscience.

As we walk the streets of independent Bangladesh, hear the anthem, or see the flag fluttering, remember that each note and colour carries the soul of young warriors like Babul. Let us keep his memory alive, not with flowers once a year, but with a lifelong commitment to justice, freedom, and truth.

Let the story of Shaheed Babul Chowdhury be passed down not as a tragedy but as a triumph of the human spirit. May he forever remain in the heart of Bangladesh—its soil, soul, and song.

The killing Grounds